A Springtime Foray into the World of True and False Morels

Intriguing species of morels and false morels hidden within the mossy landscapes of New Zealand's Kepler Track.

As I meander through a lush carpet of moss and fallen beech tree remnants near Dock Bay on the Kepler Track in Te Anau, the spring sun dapples the ground around me. Mushroom hunting has become a subtle art in these down months, but the forest still offers its secrets to those with patience and a keen eye.

I come across a cluster of Gyromitra tasmanica, the Southern False Morels, nestled at the base of a decomposing tree stump. Two large specimens, nearly the size of my hand, stand atop a fallen trunk.

What hazards are associated with the consumption of Gyromitra?

As enchanting as these false morels may be, it is crucial to recognize their potential danger when consumed. Symptoms range from nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain to confusion, seizures, and coma.

Though reminiscent of the highly coveted true morels, these intriguing fungi harbor a deadly secret: they contain the toxin gyromitrin, which produces monomethylhydrazine or MMH, a key component in rocket fuel.

As I examine the thick, orangish-pinkish, and somewhat flattened stipe of the G. tasmanica, I notice some branching near the cap of two minds as if attempting to sprout two heads. The convoluted folds of the morel's form, each a singular work of art.

Gyromitra infula, also known as the elfin saddle or hooded false morel, makes its appearance in the same mysterious world of false morels. This peculiar fungus sports a saddle-like shape, with lobes protruding above the fruiting body as if donning a cap for a woodland masquerade.

In the realm of true morels, some research has been conducted on native New Zealand species, but online forums and social media posts suggest they exist in wood chips at local city parks and gardens.

In a reading given to the Philosophical Institute of Canterbury in 1880, J.B. Armstrong recounted the discovery of Morchella esculenta in the Christchurch Botanic Garden.

Armstrong speculated that other Morchella species might eventually be discovered in New Zealand, though whether morel foraging would become a profitable endeavor remained uncertain.

My time spent in Stewart Island led me to the Rakiura Museum. In there, I met with the curators of the museum, and they brought out dusty boxes that had been stashed in the corner, waiting to be digitized.

Inside the box were over 150 paintings from the early 1900s by Dorothy Jenkin, an Oban resident who lived to 98, and went blind towards the end of her life. What remained were beautiful mushroom paintings of what she found on the island. One caught my eye, a True Morel.

As I covered a lot of the south island during the spring, after a few years of searching for the elusive native morel, I came upon a needle in a haystack. The species was sequenced and determined to be Morchella tasmanica, a first record in the country.

First recorded over a hundred years ago in Tasmania, Australia, the spores hitch a ride over the "Ditch," aka the Tasman Sea, caught in the Roaring 40s.

Many spores catch a ride, and as rain clouds form, the spore is the nuclei of a raindrop that lands on New Zealand's west coast.

As I ponder the possibility of native New Zealand morels being cultivated in the future, I can't help but marvel at the vast and intricate world of fungi hidden beneath the forest canopy.

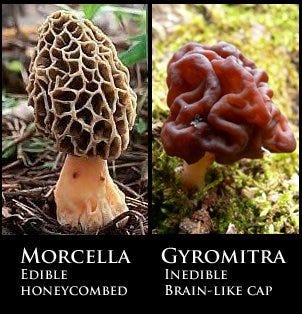

How to tell the difference between true and false morels?

One must examine their structure to differentiate between true and false morels, noting the absence of filler in true morels and how the cap attaches to the stipe.

True morels are hollow with no filler inside, whereas False morels will tend to have a cotton-like texture on the inside.

False Morel caps are typically attached about halfway down the stipe.

An edible morel's stipe is attached to the bottom of the cap.

With false morels, the stipe comes up to the top of the cap, with the top folding over on top of the stem.

Cutting morels in half is always a good practice to ensure other critters, like slugs or springtails, aren't munching away.

As the seasons shift and the warmer months bring new life to the forest floor, the elusive and fascinating world of mushrooms continues to captivate and challenge those who seek to uncover its secrets.