Encountering Fungi: How Timothee Mendez Made Mushrooms His Medium

From field forays in Mexico to macro shots of Cordyceps in caves, Timothee Mendez blends science, culture, and storytelling in a fungal journey like no other.

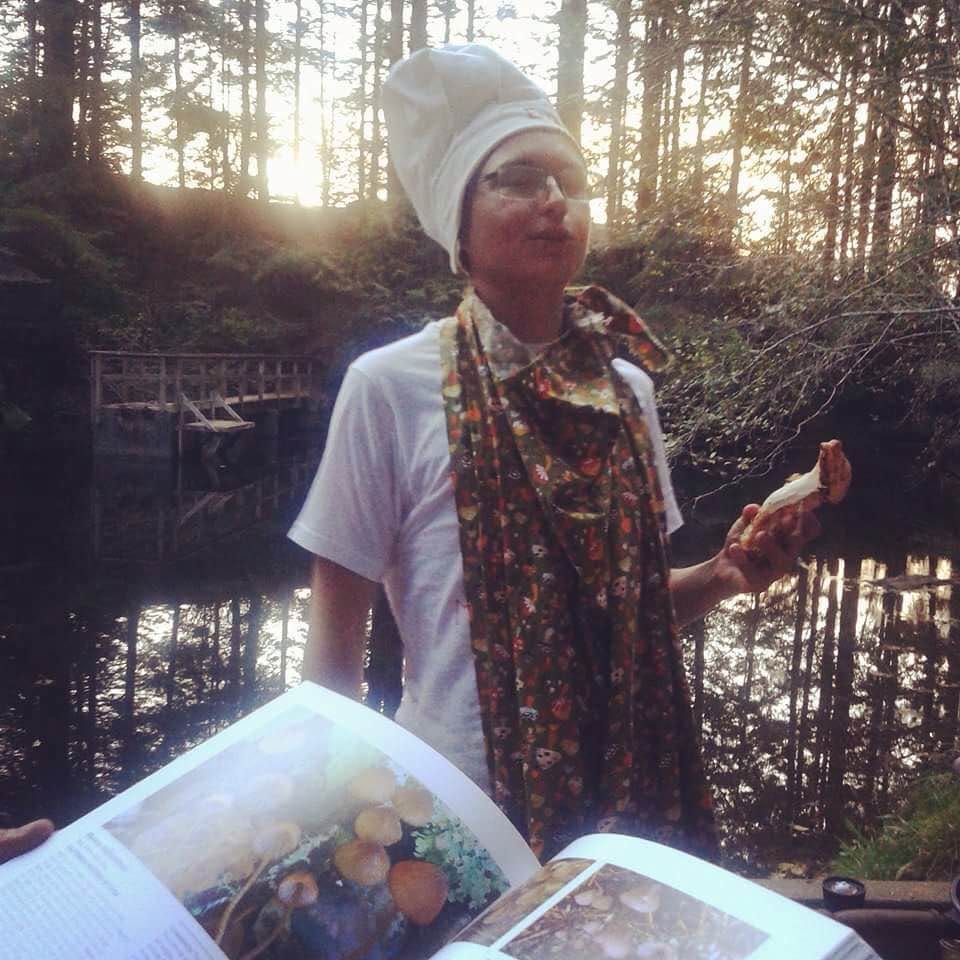

Meet Timothee Mendez. You’ll find more than food at Encountering Fungi. He studies mushrooms, writes about them, consults on projects, and shoots macro photos with focus stacking.

He digs into where names like chanterelle come from and what they reveal. He’s helped chefs, restoration ecologists, and labs apply fungal science.

In his “Names of Mushrooms” series, he breaks down the history and culture behind each name. Learn how he picks the next mushroom to feature. Discover the technical challenge, like mastering focus stacking, that shaped his photography and the image he’s proudest of.

See how he balances writing, consulting, and macro photography. Read about a field encounter that shifted his perspective on fungi. Uncover the ecosystem roles most people overlook. And finally, get his top tips for starting in mycology.

You're from Mexico, led a mycology club in California, and hunted mushrooms across North America and Europe. How has that shaped your work?

I left Mexico for the United States when I was 4 and always maintained a strong tie to the country and culture. My father is from the northern Mexican state of Sinaloa, and my mother is from France, meaning I grew up in a very multicultural environment.

This said, after living most of my life in the United States, including my most formative years, I am no doubt culturally very American despite not having residency or papers in the country.

Regarding my experience in mycology, well, that all started while studying at Humboldt State University in northern California. Within the first couple of weeks, I attended a mycology club meeting and was hooked.

I was already into botany and had done a peek into the world of mushrooms, but only superficially. The mycology club, comprising eccentric and knowledgeable personalities, became the hub of my social community during my studies there, until I eventually became president of the club. We did routine walks and trips to the nearby mountains looking for all sorts of mushrooms. We also did a bit of cultivation workshops.

This part of the world is really a mecca for mushrooms, as it has a mushroom season 365 days a year if you know what you’re doing. Temperatures rarely fall below zero, there’s moisture year-round, and there’s a diversity of habitats and altitudes at an arm’s reach.

After graduating, I genuinely tried to stay in the country and sought potential work opportunities. This proved somewhat challenging in the environmental field (the focus of my studies), given my visa status.

Most of my peers secured jobs working in government agencies or non-profits, both of which typically only hire non-citizens in exceptional cases, and not usually for entry-level positions.

After several interviews in the private sector, I realized it would be significantly challenging to secure a work visa. Despite these potential employers wanting to hire me, the challenges of the immigration system made it difficult, especially since they were looking to fill these positions as soon as possible.

Dispirited by the job search, I decided to return to Mexico and see what life I could make for myself there. I went back to Mexico and eventually traveled through Central America, and eventually found myself working at an Environmental Education center located in Costa Rica.

There, I helped in many areas, including teaching courses related to mushrooms and permaculture. For several years, I went between there and Mexico, always looking for mushrooms along the way. I regularly visited Mexico during the summer mushroom season to attend mushroom festivals and travel around the country looking for mushrooms.

Mushroom season in Mexico (about June-September) is fantastic for many reasons, but one of which is that the country is incredibly diverse.

Mexico has the highest biodiversity of Oak and Pines, two plant genera recognized for their ability to form ectomycorrhizal relationships with fungi. You get an exciting mix of tropical and temperate species in the country, many times in the same environments, meaning you get an incredible plethora of plant and mushroom species.

You also have some of the most mycophilic cultures on the planet, who have ancestral traditions of gathering and cooking many wild mushrooms, making mycology an exciting cultural and gastronomic experience.

For example, the Tlahuica-Pjiekakjoo communities in central Mexico recognize and consume nearly 200 mushroom species. Many communities host mushroom festivals during the rainy season, which are exciting places to learn and meet locals and very talented amateur and professional mycologists.

When the pandemic began, I was in Costa Rica working at the environmental education center I mentioned earlier. With the inability to receive guests, the place had to close down, and I decided to look for work online as a freelance writer.

I had always enjoyed writing and decided to sign up for various freelancing platforms and apply for gigs. With no portfolio or experience, I managed to secure some tedious and low-paying jobs writing about numerous environmental topics. Slowly but surely, I started raising my rates and finding more serious clients looking for quality work.

The pandemic was actually kind of a boom time for this, as many people had extra time on their hands and needed writers for their “pandemic projects.” Throughout the years, I’ve written a significant amount of content for blogs, websites, magazines, and internal documents for private companies and non-profit organizations. Since 2020, freelance writing has been my primary source of income and has given me the flexibility to travel and work from anywhere.

In 2022, I went with my ex-partner to Europe, where I spent over a year traveling while continuing my freelance writing gig. We did a bike tour of over 2,500 km traveling through Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovenia, Italy, and France.

In Germany, I got to try the Pheasants Back Polypore, in Poland, I tasted Macrolepiotas for the first time, in the Czech Republic, I had extensive conversations with the mycophiles of the region, and in Italy and France, I routinely saw the presence of wild mushrooms in the cuisine.

In France, I also attended various mycology-related events, including a 4-day mushroom festival in Normandy. It was the 60th anniversary of this event, and it was truly incredible to be part of such a well-developed and organized gathering, full of mycophiles with niche traditional and scientific knowledge.

I was impressed to learn that many of the mycologists in France were doctors or medical professionals, due to a legacy of mushroom identification being taught in their studies.

Historically, people could take mushrooms to pharmacies in France to verify the edibility of their harvests, meaning mushroom ID courses were required for pharmacists.

Outside of the mushroom season, I volunteered in numerous dairies in Spain and France, where I worked with animals and made cheese. I’ve learned a lot about the fungal microbiome of cheese as well. My ex-partner is an expert cheese maker.

Your “Names of Mushrooms” series goes into each name’s history and culture. What made you start exploring fungal etymology? How do you choose which mushroom to feature next?

Indeed, in my blog, you can find various texts in the “Names of Mushrooms” series. Some of these are admittedly prematurely published as they require a bit (quite a bit in some cases) of polishing.

These are texts that I have written when I’ve had gaps between work and something I do for my own pleasure. Eventually, I would like to publish these in a book. I’m working on this slowly, but it can be hard to find the time when I have paid writing gigs pending.

Considering I already spend enough time behind the computer, I usually like to spend any time outside of my projects walking through the woods or working in my garden. I’ve been told I should try and find a publishing company and make a contract to write the book, but it’s not something I’ve looked into seriously. If anyone has experience with this and likes the work, please feel free to reach out!

You upgraded your gear for focus stacking early on. How has that changed your style, which technical hurdle taught you the most, and which shot are you most proud of?

For a long time, I primarily used my phone for photography. I actually got a lot of great shots with a simple smartphone, and this got me started in my photography journey.

I had a DSLR, which was gifted to me, but without a macro lens, you can only get so far photographing fungi. Eventually, I got a macro lens and a tripod for my Nikon D3200 and managed to take slightly more “professional” shots.

I spent about a season and a half with this equipment, utilizing a small aperture and long exposures to get a nice depth of field with the shots. I initially used a focus rail for stacking, but soon realized the benefits of a camera that can do focus bracketing internally, and saved up for this.

This is a brilliant shot I got simply by utilizing my cell phone. I placed a black piece of cloth in the background for contrast and utilized a foil reflector to illuminate the gills. It came out fantastic.

About two springs ago, I went to the United States to go mushroom hunting and decided to upgrade my gear. After landing in San Francisco, the first thing I did was go meet two individuals from the Facebook marketplace to purchase a used Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II and an Olympus M Zuiko 60mm macro lens.

I was very fortunate to get a good deal on these since the sellers were motivated by my work. It honestly took a while to get the hang of focus stacking, but I eventually figured it out. It’s a bit tedious due to the quantity of post-processing needed, but it’s well worth the results.

I’m still learning A LOT about the art, especially extra details in the post-processing that I’m not entirely fluent in.

How do you balance art and scientific accuracy in each image?

I don’t really. Many of my favorite shots are simply artistic, trying to find the best angle and lighting for the most impressive and stunning image. In these shots, I’m not necessarily trying to get every detail or diagnostic identification feature.

I always attempt to take the shots in the most natural and intact environmental conditions, although in some cases I may move things around or place a mossy log in the background.

If I need some shots to identify the specimens, I’ll take some quick shots to review them later. Now, when I know I’m dealing with a unique species, that is rare or undescribed, I’ll take more taxonomy-oriented photos.

This usually involves finding multiple prime specimens so that I can display the morphological diversity expressed by a single species.

Afterwards, I lay them out in a way that all the unique features of the mushroom can be displayed appropriately.

Fieldwork can catch even seasoned mycologists off guard. What encounter in the wild shifted how you think about mushrooms?

One of the wildest mushrooms I had the chance to photograph, I didn’t find myself. I wasn’t even there when it was discovered.

I was working one sunny January afternoon when I got a call from a close friend of mine, Robert Kelly, who is a specialist on Cordyceps mushrooms.

For those who don’t know, Cordyceps are the so-called “zombie mushrooms” that parasitize a wide diversity of insect species.

These are more accurately known as entomopathogenic fungi, as they encompass a diverse lineage of fungal species. I’ve had a lot of fun photographing Cordyceps, and finding them is a whole thrill of its own!

Anyhow, when I answered the phone, Robert was intoxicated with excitement and overflowing with joy. I could barely understand him under the veil of his exhilarated delirium. This isn’t unusual for Rob, who has an eccentric personality, but this time I could tell he was REALLY excited.

He continued to explain that his friends saw something incredible in the depths of a cave, not too far from where we live. They claimed to have found a tarantula infected by cordyceps!

Not only is this an ominous place to find such a haunting duo, but it’s an extremely rare sighting. Cordyceps that infect tarantulas are mainly known from the Amazon Rainforest and other lowland tropical ecosystems.

They had never been documented from this high-altitude region of central Mexico, where we live, and where Robert has been documenting Cordyceps for over half a decade.

Several hours later, Robert and I made our way to the entrance of the cave near an old abandoned railroad line. Our canine companion, Suauripa, dared not enter the dark abyss and awaited outside like a noble bodyguard.

Feet first, we entered a hole just big enough to fit, and crouched down to make our way through the volcanic tunnel formed by the ancient flow of lava. With flashlights in hand, we made our way through passageways and rooms carved of sharp volcanic rock.

It’s difficult to calculate the distance, as we walked slowly and carefully, but about two hundred or so meters into the cave, in complete darkness, we found a fiery orange tarantula sitting on a rock ledge as though it had been placed there by the cordy-god herself.

To my surprise, the Tarantula's color had been completely transformed. Instead of its typical brown-earth tone, it looked like it had been refashioned by the costume designer of the original Oompa Loompas.

While orange is a standard color for many Cordyceps fruiting bodies, I’d never seen them transform the color of their host. Cordyceps militaris, a cultivated and medicinal species, exhibits bright orange coloration. Its mycelium also turns orange when exposed to light.

In the case of the Tarantula, it still impresses me that even the fine hairs on the specimen looked like they had been bathed in turmeric.

The Tarantula also had small orange fruiting bodies that grew from its abdomen, thorax, and legs. These fruiting bodies were perfectly ripe and were actually discharging microscopic spores that we could see glimmering in our lights as we did the photoshoot.

Like most ascomycota, Cordyceps eject their spores with significant force. I have a different video of this from a Cordyceps I found in Portugal.

Photographing it was a bit challenging. To begin, I had to utilize artificial lighting, which requires proper care to avoid an excessively synthetic look and sharp contrasts.

The sharp, rocky texture and irregular surfaces of the cave also made positioning my tripod difficult. Had I been more prepared or had more experience, I probably could have done this fungus more justice. Even still, I got some pretty good shots. We determined this was likely in the Cordyceps nidus complex.

Fungi do more than taste good or look cool. Which ecosystem or industry role do you wish more people understood?

I think people should appreciate fungi just for existing and being part of the amazing biodiversity we find on our planet.

All living things today represent the growing tips in the tree of life – the most recently evolved organisms of vast lineages that have survived countless extinction events.

That alone is amazing and of immense value.

Also, every fungus plays a unique role in ecosystems. Some help cycle nutrients from dead organic materials, while others form obligate relationships with plants. Most plant species, for example, depend on mycorrhizal fungi, and in some circumstances, even allocate close to half of the carbon they produce from photosynthesis to them.

Many fungi also provide unique food sources to niche insects and animals. In some cases, this can be quite significant, such as the western Flying Squirrels from the Pacific Northwest, which eat up to 20 different species of truffles that can compose 80% of their diet during certain times of the year.

I think when it comes to food, the “functional” aspect of mushrooms is something that’s not widely understood.

Essentially, eating mushrooms is REALLY good for you. Edible mushrooms produce many secondary metabolites that improve immune health, cognitive function, and overall well-being. For example, many mushrooms have ergothioneine, an amino acid that acts as a very potent antioxidant.

In a couple of clinical trials, it has been shown to improve cognitive function and potentially even help prevent cognitive decline in elderly individuals. Ergothioneine is unique because our cells have unique uptake mechanisms specifically designed for it.

We can actually store Ergothioneine and utilize it in times of high oxidative stress. This is unlike any other antioxidant. Ergothioneine is almost exclusively found in fungi, and it’s only found in plants due to their associations with mycorrhizal or endophytic fungi!

I’ve studied the health benefits of mushrooms quite a lot. I have a website called mushroomclinicaltrials.com, which is a compendium of the clinical research that has been conducted on functional mushrooms.

I believe there's a lot of misleading hype surrounding mushroom supplements, but I also recognize their potential health benefits and therapeutic applications. They will rarely cure anything on their own, but they can be part of a healthy lifestyle or holistic treatment.

I personally have experienced positive benefits from Reishi and Cordyceps mushrooms. For transparency, I do promote certain vetted, high-quality, and reputable products on my page and do receive a commission.

How do you stay on top of so many topics? Which resources or habits keep you learning?

The internet is a fantastic tool, but it’s so full of junk content. It can be difficult for anyone to navigate the vast amount of low-quality and false information that exists here. This is particularly evident now with the advent of artificial intelligence, but honestly, there was a lot of slop already before this. This is why finding credible resources is so important.

For identification, I often utilize David Arora's "Mushrooms Demystified" or Michael Kuo's website, mushroomexpert.com, as an entry point.

These are AMAZING resources, although they have their limitations, especially considering the evolving world of mushroom taxonomy. Since there are few comprehensive guidebooks in Mexico, and none for my specific region, these are often a good start.

The United States, Europe, and Asia have TONS of excellent guidebooks, something you shouldn’t take for granted if you live in these areas!

If I need a further opinion, I might refer to Index Fungorum, which is the very best place to find updated information about the most recent taxonomic changes. It can also be really useful because many species on there have links to the original descriptions. These are the descriptions that have the ultimate authority about whether the species name is accurate or not. It’s incredibly common that species names are misapplied.

Obviously, inaturalist.org is also extremely useful, but users should also be aware of its limitations and errors. This is especially true for rare or unique species. I know for sure there are a handful of taxa on there whose “profile” has been built around erroneous identifications that do not align with original descriptions set out by the authors. This isn’t a harsh criticism towards the platform, as I think it’s fantastic, but users should understand that it’s a sort of “work in progress,” especially as fungal taxonomy gets sorted out.

Lastly, I’ll search the scientific literature a lot using Google Scholar. Here you can get access to thousands of peer-reviewed research papers on almost any subject you want. Some of these can be highly technical, but if you look carefully, you can often find some more approachable texts about general topics.

I also really enjoy reading old mushroom books (I saw tons of these in Europe), or I utilize a digital database like archive.org, where you can find many digitized books.

Old texts like this can be really interesting to gain unique insight not found on the rest of the internet. The way I see it, a considerable portion of the internet is like an unregulated game of telephone. Information simply gets regurgitated over and over again from one blog to another, and eventually to social media and beyond. In contrast, books can contain novel information that either hasn’t entered the “autophagic” metabolism of the internet.

Additionally, I’ve subscribed to nearly every mycological society's YouTube channel I could find. This provides me with a decent feed of lectures and talks that I can tune into when I want to learn something new. I also really enjoy The Mushroom Hour Podcast, which has some brilliant interviews.

If someone is just starting out with mycology or mushroom photography, what practical tips would you give on identification, field technique, or making connections?

The best way to learn something is to find people who are already doing it.

Hopefully, they are nice and you can befriend them. Look for a local mycological society, go to a mushroom festival, or simply convince anyone you meet who knows more about mushrooms/photography than you to let you tag along. Having a good teacher, in person, is the fastest way to learn any skill.

For photography, practice makes perfect.

I’m still learning a lot every time I go to the field. When you're first getting started, it can really help to stage some shots in your home, especially if you're unfamiliar with and utilizing a DSLR camera.

It’s well worth it to familiarize yourself with your gear in the comfort of your own home, instead of troubleshooting out in the field when there are mosquitoes, rain, and ominous thunder that’s creeping up on you.

Where will you take Encountering Fungi next? What new series, consulting projects, or collaborations are on your roadmap? How can people connect with you?

Encountering Fungi is a bit of my personal website, but also a portfolio for my freelance writing gig in the mushroom niche. While I’ve been pretty fortunate to have consistent freelance work, I have noticed a significant decline in demand. This started at the end of the pandemic and then more so after the release of AI chatbots.

While the general decline in writing gigs has been a bit worrying, I honestly see it as an opportunity. A lot of the work that AI is replacing is the low-tier, low-paying gigs. This is generic writing work that people don’t really want to pay much money for, to begin with. I admit, I’ve done a lot of this work. I offer relatively affordable rates, and my writing isn’t necessarily published in prestigious magazines, newspapers, or journals.

This said, I’m motivated to expand my writing into new frontiers. This could mean trying to get a book contract or simply pitching to more respected publications. I’ve had a tiny bit of luck pitching articles, and while I rarely get responses, that’s just the nature of the game, from what I understand.

I really like the idea of moving more towards a journalistic writing style and writing about topics that sincerely interest me, like fungal ecology and conservation. Since these gigs tend to be a bit better as well, it gives me the liberty to really focus and invest in creating a written piece of art. At the very least, the clients I am able to maintain are genuinely interest in having high-quality and human-written content.

If anyone wants to contact me, they can do so via email at timendez@gmail.com. You can also view more of my photos on Instagram at @organicultura or on my website, encounteringfungi.com.

Hola, Timo and Joseph—Thanks for such a well-written article and fantastic photos. I live in Baja Sur, Mexico on the Pacific coast; our village has a direct road to the Sierra de la Laguna. There is a rare, endemic oak in the peaks, as well as many other endemic species, plus newly catalogued insects. I don’t know of any mycologist who has explored this range. While I am physically unable to do mushrooming anymore, I would like to learn more about species here and Mexico in general, including cultural uses. (I also did freelance writing, grant writing and photography.) Timo, if you ever want to visit this area, I will clean up our spare bedroom and loan you our old 4WD.

Great interview, and a lot of great stories. I found myself physically leaning forward during the adventure to find and photograph that tarantula. Stunning stuff. Keep it up, both of you.