Fungi in Food Technology: Innovations, Challenges, and Sustainable Solutions

Explore how fungi are revolutionizing food and biomaterials with PhD student Josie Krepps. Learn how fungal mycelium is advancing cultivated meat, tackling global food challenges, and more.

From Hydrogels to Fungi: My Path to Alternative Proteins

What inspired you to pursue food mycology, and how did your interest in fungi as a biomaterial begin?

As I narrowed my search for PhD programs last year, I had a few nonnegotiables: the program title must include "food,” the research project must have a sustainability component, and I had to be compatible with my advisor.

Based on those criteria, I applied to seven programs in food science that offered projects in alternative proteins, waste valorization, and agricultural sustainability; only one of those projects focused on food mycology, using fungi as a biomaterial.

My interest in biomaterials came before my interest in fungi, though! As an undergraduate researcher, I worked with hydrogels, which are water-based, semi-solid materials used in biomedical research and tissue engineering. They look and feel a lot like gelatin!

My first exposure to mycology was a close friend of mine who picked up mushroom foraging in college. I’ve never been a fan of the outdoors, and I couldn’t understand why he was so interested in fungi. I never thought I’d become a mycologist myself (albeit an amateur one).

2. Can you share a bit about your journey as a PhD student working on alternative proteins? Have you made any unexpected discoveries or encountered any challenges along the way?

Alternative proteins are food technology alternatives to conventional protein, and they can be plant-based, microbial-based, cell-cultivated, or even things like insect protein.

Alternative protein scientists call it “alt protein” for short.

I started in alt protein in June 2022 researching cultivated meat, which is meat grown from cells rather than farmed from livestock. I was an undergraduate researcher in the chemical engineering department at Lehigh University, where I earned my B.S. in Integrated Natural Science and Engineering in May 2024.

I was very lucky to land in a PhD program that both met my criteria and expanded on my undergraduate work—it’s not typical to perform graduate research on a topic you’ve studied before, so I had a bit of a head start.

Alt protein is an extremely small but fast-moving community, which I really enjoy. The novelty keeps me motivated in my own work. A lot of alt-protein researchers have also pivoted from biomedical fields to food, which brings a fresh perspective to the research.

Fungi in Food Technology

How does fungal mycelium compare to other alternative protein sources in terms of sustainability, scalability, and nutritional benefits?

Let’s start with some background to set the stage.

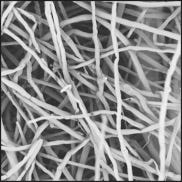

I use fungal mycelium as a “scaffold” for animal cells to grow cultivated meat. Scaffolds are 3D networks that provide structural support for cells; they make up the “fibrous” or “stringy” part of meat.

Think about the texture of ground beef vs. a ribeye steak; a steak has marbled muscle and fat, while ground beef is more of a mixture. Scaffolds are important for achieving that “structured” meat texture.

Other competing scaffolds in cultivated meat are hydrogels (which I researched in my undergraduate work), plant-based scaffolds like spinach leaves and soy, bacterial cellulose (used to make paper), and some animal-derived materials like gelatin or collagen.

In terms of cost, plant-based, fungal, and bacterial scaffolds are the cheapest; synthetic scaffolds like hydrogels are extremely costly, and animal-derived scaffolds will have to be made with expensive recombinant DNA technology since the ultimate goal with cultivated meat is to reduce animal slaughter.

Recombinant DNA technology means making collagen by taking the collagen-encoding DNA from an animal, giving the DNA to a controlled cell type (usually a yeast or bacterium), and then synthesizing large amounts of collagen without the need for the animal.

Soy has recently become a popular scaffold choice in academia, but it’s a known allergen that could prevent a large segment of the population from eating cultivated meat.

Bacterial cellulose and plant-based scaffolds are promising candidates because they add nutritional value to the product compared to a synthetic scaffold, but preparing these scaffolds can be costly; a lot of processing and treatments are needed to take a spinach leaf and make it into a suitable scaffold.

That’s where fungi come in—we can grow fungal scaffolds in just a few days, and little treatment is needed to prepare them because the mycelium already has that “fibrous” shape that we want for meat! Fungi also add nutritional value to the product, and they can be grown on agricultural waste streams like sawdust and coffee grounds, helping to create a circular food system.

What unique properties of fungi make them especially suited for creating alternative proteins?

There are three major benefits to using fungi for alternative proteins:

fungi have a comparable protein content to animal meat

they naturally create a fibrous structure similar to that of whole-cut or “structured” meat products, and

they grow fast! This makes fungi a nutritional, sensory, and affordable hero for alt protein.

You might have heard of Quorn, a fungal-based protein available in most grocery stores in the freezer aisle. Quorn is made using extremely large cultures of Fusarium venenatum, and by itself is a complete protein—meaning it contains all 9 essential amino acids!

Can you explain how changing species, growth conditions, or heat treatments can alter the material or taste properties of fungal-based proteins?

While my interests are in alternative proteins, another major reason I’m using fungi as a scaffold is to investigate the effect of evolutionary diversity on material properties.

Are fungi that are farther away on the evolutionary tree just as different in terms of material properties?

Do species from one family produce denser, stiffer scaffolds?

These are questions that help drive my research beyond just food.

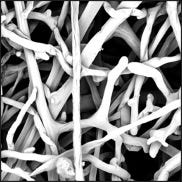

Changing species can have profound effects on material properties. Preliminary data for my project, conducted by another student about a year ago, demonstrated that two species far apart on the evolutionary tree, Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Rhizopus oryzae, had different material properties. Generally, species that grow denser mycelium will be stronger, which affects their texture when eaten.

Another option is to vary growth conditions for the same species to see how material properties and morphology (shape or form) change.

Fungi grown in submerged media vs. in a flat, square dish at the air-liquid interface can result in dramatically different morphologies!

Changing nutrient composition can also change morphology; this study demonstrated that Ganoderma lucidum grows radially when supplemented with lignin, a structural component in the plant cell wall; the same species grown without lignin had randomly distributed growth.

Fungi Beyond Food: Biomaterials for Packaging, Fashion, and Construction

Beyond food, how do you see fungal biomaterials being used in fields like construction, packaging, or even fashion?

Several companies like Ecovative Design, MycoWorks, Bolt Threads, and Myceen are working in these areas using fungal mycelium to make leather, bricks, food packaging, and even biomedical scaffolds for health research.

Fungal biomaterials are cheaper and more sustainable than petroleum-based plastics—it’s just a question of finding the right species and tuning the properties for the target application.

What are the most exciting applications of fungal mycelium that could transform the food industry in the next decade?

I’m biased to say fungal mycelium for cultivated meat, but that’s realistically a very small corner of the food industry. I think fungi for food packaging could get pretty big in the next 10-20 years.

We could build antibacterial, cheap, sustainable food packaging, all while creating a circular economy.

A lot of research is still needed to identify the right species and growth conditions to make packaging suitable for different kinds of foods, though.

What role do you think fungi can play in addressing global issues like food insecurity, environmental degradation, or climate change?

You’ve probably heard of mycoremediation—using fungi to remove pollutants from the environment. Fungi have been shown to be capable of removing oil and heavy metals from soil and water. Some fungi can even break down plastics.

While these are promising results, the one problem is that the contaminant usually remains in the fruiting body of the fungus and will have to be disposed of, likely in a landfill.

Because fungi are so resilient and fast-growing, they can be great options to combat food insecurity in low-income areas. A past project, “GRO Mushrooms,” at my alma mater, Lehigh University, developed a commercial oyster mushroom production system for use in Sierra Leone, Africa. There are still lots of opportunities for developing large-scale mushroom cultivation systems still out there.

Advancing Fungi-Based Proteins: Insights from My Current Work

Could you share some highlights from your current research on fungi-based proteins? What aspect excites you the most?

Generally, fungal scaffolds are unexplored for my niche in cultivated meat. There are only a handful of researchers who have published in this space so far, but the results are promising.

Animal cells have been shown to grow, proliferate, and differentiate on fungi, and we’re working to understand how we can specifically tune material properties of mycelium to better support animal cells and recapitulate the texture of conventional meat.

Are there any specific species of fungi you work with regularly? What makes them ideal for your research?

Because the end goal of my work is to produce cultivated meat, I work with “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) fungal species. These are fungi that have been used in the food industry for many decades (or longer) and recognized by the FDA as safe for consumption, like Aspergillus oryzae (soy sauce fermentation), Rhizopus oryzae (fungus in tempeh), Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom), and other edible species that produce mycelium.

Have you experimented with “unconventional” fungi or species that surprised you with their properties?

I personally haven’t—in science, we try not to run into surprises! The species choices for my project are very intentional, based on food safety, evolutionary diversity, and projected material properties. I’m certain there are commercial products made from unconventional species, but a lot of that information is proprietary and kept internal. Generally, fungal biomaterials are about as mechanically strong as foams.

The diversity of the fungal kingdom continues to surprise me though, like the zombie-ant fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis (featured as a mutant in The Last of Us)!

Overcoming Barriers: Taste, Texture, and Cultural Acceptance of Fungi-Based Foods

What are the biggest challenges in making fungi-based foods appealing to consumers (e.g., taste, texture, cultural acceptance)?

Texture and appearance are major scientific obstacles.

Humans are extremely good at detecting small textural differences in food, especially foods we eat frequently and in large portions, like meat.

“Good enough” isn’t really good enough for consumers; alternative proteins need to taste like meat if we want people to buy them. And, of course, they need to be cost-competitive or cheaper than conventional meat. Mycelium can definitely help close the texture gap.

Public acceptance will be harder to achieve. A lot of people perceive cultivated meat and other alternative proteins as “ultra-processed” foods. A food being processed doesn’t inherently make it bad or unhealthy—chocolate, alcohol, protein powder, and packaged foods are all “processed,” but their nutritional value doesn’t come from being processed. Several states and countries have preemptively banned the sale of cultivated meat, including Alabama, Arizona, Florida, and Italy.

What innovations or breakthroughs in fungal biomaterials are you hoping to see in the near future?

I would love to see more work using fungal mycelium to reduce e-waste!

Electronic waste, or e-waste, has a large margin for waste reduction, and we haven’t really figured out how to cut down on waste from circuit boards, microchips, sensors, and other electronics. There are few available recycling streams for phones, computers, printers, large batteries, heavy machinery, and other devices. As an electronic tinkerer myself (I build custom mechanical keyboards), it would be amazing to have access to more sustainable electronics.

Are there misconceptions about fungi-based proteins or biomaterials that you’d like to address?

From the fungal perspective, a lot of people think foods made with fungal mycelium are (bad) mold, forgetting that their blue cheeses and bloomy cheese rinds are full-on mold (that you can safely eat).

Many U.S. government agencies, farmers, and meat producers feel threatened by cultivated meat and alternative proteins. Realistically, I don’t expect that cultivated meat will completely phase out conventional animal meat, but we need to invest in diverse protein sources to build a robust food supply.

Pandemics, global conflict, and climate change are all threats to our food supply chain; with alternative proteins, we can relieve stress on the food system, mitigate climate change, and combat food insecurity. It can’t hurt to have more protein options available to consumers.

How to Get Involved in Alternative Protein Research

How can readers learn more about fungi in food technology? Are there any resources, organizations, or projects you’d recommend?

I love the Controlled Mold blog about fungi in food! I believe one of the authors is on paternity leave, so there aren’t many recent posts, but they have great content on fungal fermentations, bioreactors, and home science.

For more hardcore food mycology, The International Commission on Food Mycology is the major professional association for food mycologists.

I also touch on food mycology and fungal food technology topics on my own Substack, Biotech Trash Talk.

If someone wanted to get involved in this field, where should they start?

If you’re looking to get into alt protein, I’d recommend searching through The Good Food Institute’s alternative protein researcher directory; there, you can find research topics spanning plant-based, microbial, and cultivated proteins and identify leaders in the field! My contact information is listed in the directory if you ever want to chat alt protein.

I’ve also found many colleagues through my LinkedIn. I’d recommend that any high school graduate or current college student make a LinkedIn page and start building their network while the community is still small. As for what to study if you’re still deciding, alt protein is an extremely diverse field that pulls from expertise in chemical engineering, bioengineering, agriculture, molecular biology, food science, and non-STEM fields like business & marketing, political science, and communications—we’ll always need good writers!

Great, super! Thanks Joe and Josie. Subscribed and restacked!

Very interesting field of research! Good interview.